The following article about Disney’s 2015 film Tomorrowland (dir. Brad Bird) will contain spoilers, and it will to some extent disagree with Emmet O’Cuana’s very good Sequart article about the film, which I recommend reading.

The following article about Disney’s 2015 film Tomorrowland (dir. Brad Bird) will contain spoilers, and it will to some extent disagree with Emmet O’Cuana’s very good Sequart article about the film, which I recommend reading.

I grew up in Cerritos, California, living there from 1968 (when I was four) until I graduated high school in 1982. Cerritos is on the border of LA County and Orange County: immediately across the border is Anaheim, which is home to Disneyland, Knott’s Berry Farm, and a number of other attractions that at one time included Japanese Gardens and a wax museum. Because I grew up so close to Disneyland it formed a big part of my childhood. I remember going there for birthdays, school outings, with visiting friends and relatives, and taking dates to the dancing waters show, which was free and had great little corners for hiding in and making out. I was always a sci-fi fan, so of course my favorite part of the park was Tomorrowland, which was part of the original park whose construction was supervised by Walt Disney and completed in 1955. I remember Tomorrowland before Space Mountain was built, when you had to use lettered tickets for different rides (the gold tickets, E, were the best), and I remember how totally cool Space Mountain was when it did open up. Before Space Mountain, Tomorrowland’s main attractions were a Voyage to Mars ride that simulated spaceflight in a large, round room, the Carousel of Progress, and a submarine ride.

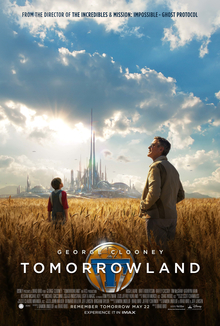

As much as I enjoy waxing sentimental about my childhood at Disney, though, I’m not doing so simply for nostalgic pleasure. Tomorrowland‘s first scene is set in 1964, the year of my birth, and it is set at the New York World’s Fair. At that world’s fair a young visionary, Frank Walker (perf. Thomas Robinson as a child and George Clooney as an adult), takes a ride on the “It’s a Small World” attraction and winds up in the city Tomorrowland — both of which allude to Disneyland without mentioning it. These clues suggest that the purpose of the film is to articulate Walt Disney’s intent for his parks, films, and for the massive industry he built on his films and theme parks. But at the same time, I’m going to argue that the film fails to serve that intent in one fundamental way in its ending, so that the problem with the film is not that it is too optimistic, but that in the end it is fundamentally pessimistic in ways that violate the film’s central premise despite its happy ending.

I grew up visiting Tomorrowland around the same time the TV series Star Trek first hit television, and both the original Star Trek series and Tomorrowland shared the same ethos: that humanity’s problems could be solved, that the world could be better, and that imagination combined with hope were the primary vehicles for individual and social change. In this sense, Charlie Jane Anders rightly identifies the film as Baby-Boomer nostalgia. Both the Carousel of Progress and the film Tomorrowland argue this thesis explicitly. In the film, the city called “Tomorrowland” was populated by visionaries, geniuses, and creative types whose function was to create, improve, and build, and by so doing, improve humanity. The film’s protagonist, Casey Newton (perf. Britt Robertson), is a young girl who shares this visionary spirit, and in her optimism and belief in progress she resists all reactionary measures, specifically and immediately the dismantling of the launch platform at Cape Canaveral at which her father (perf. Tim McGraw) works.

She soon comes into contact with a small pin with a red letter T on it, and touching that pin allows her to travel, at first only mentally, to the world in which the city of Tomorrowland resides. However, she is soon found by, pursued, and nearly killed by robotic agents of Governor Nix, whom we soon learn rules Tomorrowland, from which the adult Frank Walker has been exiled. Something is terribly wrong, but the young, android girl Athena (perf. Raffey Cassidy) who first recruited Walker has now also recruited Casey in the belief that she could fix what was wrong with Tomorrowland.

Once there, Walker, Casey, and Athena learn that earth will be devastated by a coming nuclear holocaust. They learn of this future using a device that sends and receives transmissions to and from earth that give them visions of the future. They soon discover that Nix is actually transmitting warnings about a coming nuclear holocaust, but that Casey’s resistance to that image actually changes the projected future, which not only implies that the future isn’t fixed, but that Nix’s warnings are having the effect of a self-fulfilling prophecy. His warnings fill the minds of those who receive them with images of a nuclear holocaust, and their apocalyptic mindset brings this holocaust to pass.

When Walker, Casey, and Athena confront Nix with this possibility, he rejects it. He believes that the human beings left on earth are capable only of destruction and self-annihilation, and that his broadcasts have nothing to do with it: the real problem is that people won’t listen. He is willing to allow the people on earth to destroy themselves, as that won’t affect the continued existence of Tomorrowland. After a struggle, the machine sending the broadcast is destroyed, and with it, Nix. The film ends happily with Walker leading Tomorrowland and sending out new recruiters to draft new visionaries. Disaster has been averted: the film’s final scenes take place one year after Nix’s defeat.

This plotline validates Disney’s intent for Tomorrowland. In the world of the film, our destruction is caused by our destructive imaginations. When we cease focusing on a world-ending apocalypse as the inevitable trajectory of human civilization, we actually manage to survive at least another year rather than just another sixty days. The film does not, of course, promise that no apocalypse will ever come, only that it has not yet. But the way in which the film fails in its own support of its thesis is in the death of Nix. The name “Nix,” of course, aside from our everyday use of the term as one of negation (“nix it”), is derived from the Greek goddess Nyx, who was born out of chaos and who stands for “night.” She gave birth to beings such as death and sleep. So in terms of the film’s symbolism, Governor Nix may well simply represent an impulse rather than a person. He represents the cynicism and despair that must be defeated for the world of creativity to flourish and serve its purposes.

But if we take Governor Nix seriously as a human character, the plot logic that kills him off is identical to his own logic. That logic prevents him from entertaining any hope for humanity and taking appropriate steps to try to save us, which in this case would have just been shutting down or destroying the broadcasting machine. In other words, the reasoning that kills the bad guy is identical to the bad guy’s own reasoning: if human beings could be allowed to think differently, why couldn’t Governor Nix? I disagree with Charlie Jane Anders’s second Tomorrowland article on this point: the film is in fact optimistic. It’s not only communicating a nostalgia for optimism because it does in fact ask of us that we share the film’s optimism and work to make change. The problem is that in its final killing of Nix it allows no place for our darker impulses, which always have a place and find expression. Inside Out was a more emotionally complex film on this point. Our choices aren’t, then, between the optimistic science fiction of the baby boomer generation or the apocalyptic science fiction more common today (which is also optimistic whenever the apocalypse is diverted). The point is that we need both, and really, that we have always had both. Utopian literature from its outset, even if we start with Plato’s Republic, posited an imaginary and likely never to be realized ideal world.

Of course the film has already been mercilessly panned for its unrealistic and, by some accounts, dangerous optimism, and it was hardly a box office success, taking in just a little more than it cost to make. The conversion of Governor Nix would have been an optimism that for most viewers would have pushed the film past unacceptable into the unbearable. So while I won’t argue with the decision to kill off Nix on aesthetic grounds, in terms of the film’s thesis that act represents a failure of the imagination. The truth is that, in our world, the players who manage the finances, businesses, and governments around the world are only human beings, and human beings can change their minds. They can have hope. What we should be thinking is that if we try to convince everybody we will convince somebody: realism dictates that some people, like Nix, will remain hopeless and negate all efforts to improve the world, but realism also dictates that some people will not, and that is exactly the reason why it is worth the effort to act as if change were possible.

But I would also like to suggest that the film’s real audience isn’t the usual Disney audience, but creative types themselves, who are not pictured living in this world but occupying a world parallel to our own. The artist is removed from society by being its spectator. Remember that Nix was Governor of Tomorrowland, home to visionaries, creators, and artists. What I think the film is registering is the despair of the artistic community over recent political and economic developments, and that its real message is to tell this community to keep doing its job. We aren’t hopeless as a species until we believe that we are, and that means that our collective imagination, above all else, needs to be able to picture a better future, not only a dying one.

Yes, unbridled optimism does serve ideological purposes by holding out continual hope in the face of continual injustice, perpetuating the system of injustice by perpetuating our participation in it.

But optimism isn’t nearly as dangerous as despair.